1934 Yiddish BOOK Judaica CHAIKOV Jewish AVANT GARDE ART Russian KULTUR LIGE

When you click on links to various merchants on this site and make a purchase, this can result in this site earning a commission. Affiliate programs and affiliations include, but are not limited to, the eBay Partner Network.

1934 Yiddish BOOK Judaica CHAIKOV Jewish AVANT GARDE ART Russian KULTUR LIGE:

$135.00

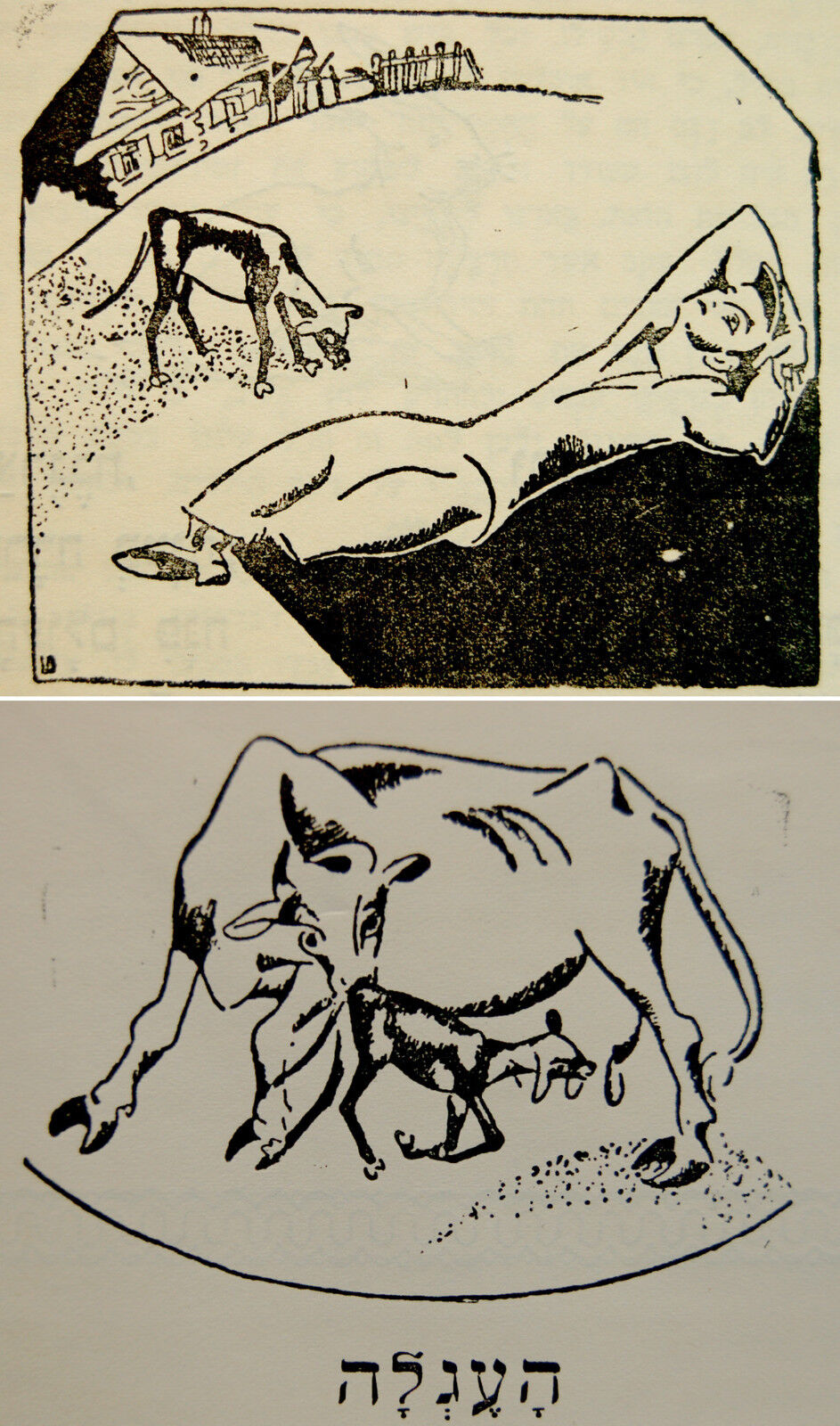

DESCRIPTION : Here for sale is a quite rare oddity - It\'s a 1934 anthology for children of Hebrew - Yiddish - Jewish - Russian pieces , Stories and poems which was published in Eretz Israel ( Palestine ) for the purpose of being a Hebrew teaching book for Eretz Israel children. The book includes among other pieces an illustrated shortened Hebrew version of \"The LITTLE CALF\" ( Dos kelbl / Mendele Moykher Sforim ilustrirt fun Yoysef Tshaykov ) by Mendele Mocher Sfarim which was originaly published by the KULTUR LIGE in WARSAW 13 years earlier in 1921 and was illustrated by the Russian Jewish Avant Garde artist JOSEF CHAIKOV ( Also Tchaikov , Tshaykov ) . A member of the \"Groupfor Jewish National Aesthetics\" in Moscow together with artists like ElLissitzky, Yissakhar Ber Ryback and others . this fascinatic artistic branch of the RUSSIAN - JEWISH AVANT GARDE included artists such as EL LISSITZKY , JOSEPH CHAIKOV , MARC CHAGALL , BORIS ARONSON , NATHAN ALTMAN YISSACHAR BER RYBACK , KULTUR LIGE artists and others .The book also includesmany VIGNETTES and small ILLUSTRATIONS of other JEWISH artists , For example E.N.LILIEN of the Bezalel School of Art in Jerusalem. Hebrew . Original cloth HC. 9 x 7 \" . 285 pp . With small illustrations and vignettes. Very good inner condition . Used. Tightly bound . Clean. The original torn spine is quite abruptly glued to the book ( Pls look at scan for accurate AS IS images ) . Will be sent inside a protective rigid envelope . AUTHENTICITY : This is anORIGINALvintage1934 ( Dated )copy, NOT a reproduction or a reprint or recent edition,It holds a life long GUARANTEE forits AUTHENTICITY and ORIGINALITY.

PAYMENTS : Payment method accepted : Paypal .SHIPPMENT : SHIPP worldwide via registered airmail is $ 17 .Will be sent inside a protective envelope . Handling within 3-5 days after payment. Estimated Int\'l duration around 14 days. Joseph Moisevich Chaikov (also spelled, among other spellings, Tshaykov, Tchaikov, and Tchaikovsky; 1888 – 1979) was a Russian Jewish sculptor, graphic designer and teacher, active both before the revolution and as a Soviet artist.Born in Kiev and initially trained as an engraver, Chaikov studied in Paris in the years 1910 through 1914. In 1912 he co-founded a group of young Jewish artists called Mahmad, and published a Hebrew-language magazine with that name; in 1913 he participated in the Salon d\'Automne.He returned to Kiev in 1914. He was co-founder, along with El Lissitzky, Boris Aronson and others, of the Jewish socialist Kultur Lige in Kiev, led sculpture classes there, supervised a children\'s art studio and illustrated children\'s books, and in post-revolutionary Kiev focused on billboards and agitational propaganda. In 1921 he published the Yiddish-language book Skulptur, advocating avant-garde sculpture as a contribution to a new Jewish art. This book was also the first book on sculpture to be published in Yiddish.[1][2]Chaikov moved to Moscow to teach at Vkhutemas from 1923 to 1930, alongside fellow sculptors Boris Korolev and Vera Mukhina. All three designed and taught cubist sculpture in the distinctively Russian Cubo-Futurism style, radically geometric and highly dynamic. From 1929 Chaikov was the head of the Society of Russian Sculptors. In 1932, after the end of the period of artistic freedom, all of these cubists turned back to Socialist Realism and produced more classically styled work.In the 1930s his work was prominently shown at the two Soviet world\'s fair pavilions, for the 1937 Paris Exposition and the 1939 New York World\'s Fair. His work in Paris was an extensive frieze of nine-foot figures, the People of the USSR, carved on two steles flanking the entrance to the pavilion. Fragments of the Paris work were unearthed in rural France in the 2000s, after having been presented to the French labor union after the fair, relocated to a holiday château, broken up by pro-Nazi youth during the occupation, and buried for 50 years.[3]Chaikov continued to work in a variety of genres, techniques and scales. He was named an Honored Artist of the USSR in 1959, and his work is in the permanent collection of MOMA.He died in Moscow.Major worksPeople of the USSR – friezes on steles flanking the entrance to the Soviet Pavilion at the 1937 Paris Exposition, for architect Boris Iofan (recently rediscovered) Bas reliefs for the Soviet Pavilion at the 1939 New York World\'s Fair, for architect Iofan The golden Friendship of the Nations fountain at the All-Russia Exhibition Centre, Moscow, circa 1954 (with fellow sculptors Z. Bazhenova, L. Bazhenova, A. Teneta, and Z. Rileeva) The Kultur Lige (Culture League) was a secular socialist Jewish organization associated with the Jewish Labour Bund, established in Kiev in 1918, whose aim was to promote Yiddish language literature, theater and culture.[1] The league organized various activities, including theater performances, poetry recitals, and concerts in Yiddish with the aim of disseminating Jewish art in Eastern Europe and Russia. Among some notable members of the organization were the scenic designer Boris Aronson (who later worked on Broadway),[2] the artist and architect El Lissitzky,[2] the writer David Bergelson,[3] the sculptor Joseph Chaikov, the writer Peretz Markish,[4] the poet David Hofstein,[5] and Isaac Ben Ryback.[2] Bergelson, Markish and Hofstein were later executed on Joseph Stalin\'s orders during the so-called Night of the Murdered Poets, in 1952.Artists like Ryback and Lissitzky who were members of the group tried to develop a distinctively Jewish form of modernism in which abstract forms would be used as a means of expressing and disseminating popular culture.[2]The manifesto of the group, published in November 1919, stated:\"The goal of the Kulturlige is to assist in creating a new Yiddish secular culture in the Yiddish language, in Jewish national forms, with the living forces of the broad Jewish masses, in the spirit of the working man and in harmony with their ideals of the future.\"[6]It also listed the \"three pillars\" of the Kultur Lige as Yiddish education for the people, Yiddish literature, and Jewish art.[7]In 1919 members of the group, Victor Alter and Henryk Berlewi, organized a major exhibition of Polish-Jewish art in Białystok under the name \"First Exhibition of Jewish Painting and Sculpture\". The exhibition was targeted at the Yiddish speaking Jewish community, as well as the Polish workers of the city. During the same year, the organization helped to sponsor sixty three Yiddish schools, fifty four libraries and many other cultural and educational institutions.[8]In 1920 the Kiev branch of the organization was taken over by the Bolsheviks and the Jewish section of the Soviet Communist party, Yevsektsiya, and subjected to the bureaucracy of the Soviet state.[6] Its printing presses were taken away, it was denied paper for publishing and its central committee was forcefully disbanded.[6] As a result, the Warsaw branch became the main center for the organization.[1]Afterward, the remains of the Kultur Lige in the Soviet Union continued under the auspices of the Yevsektsiya as a publishing house, mostly focusing on Yiddish textbooks for children. In Poland, the League established offices in other cities such as Wilno and Łódź. In 1924, it began to issue the Literarishe Bleter magazine (based on the Polish Wiadomosci Literackie) (Literature News) which became the main forum for discussions by the Yiddish intelligentsia on subjects of art, literature and theater.[8] The Yiddish Book Collection of the Russian Avant-Garde contains books published between the years 1912-1928 by many of the movement’s best known artists. The items here represent only a portion of Yale\'s holdings in Yiddish literature. The Beinecke, in collaboration with the Yale University library Judaica Collection, continues to digitize and make Yiddish books available online.With the Russian Revolution of 1917, prohibitions on Yiddish printing imposed by the Czarist regime were lifted. Thus, the early post-revolutionary period saw a major flourishing of Yiddish books and journals. The new freedoms also enabled the development of a new and radically modern art by the Russian avant-garde. Artists such as Mark Chagall, Joseph Chaikov, Issachar Ber Ryback, El (Eliezer) Lisitzsky and others found in the freewheeling artistic climate of those years an opportunity Jews had never enjoyed before in Russia: an opportunity to express themselves as both Modernists and as Jews. Their art often focused on the small towns of Russia and Ukraine where most of them had originated. Their depiction of that milieu, however, was new and different.Jewish art in the early post-revolutionary years emerged with the creation of a secular, socialist culture and was especially cultivated by the Kultur-Lige, the Jewish social and cultural organizations of the 1920s and 1930s. One of the founders of the first Kultur-Lige in Kiev in 1918 was Joseph Chaikov, a painter and sculptor whose books are represented in the Beinecke’s collection. The Kultur-Lige supported education for children and adults in Jewish literature, the theater and the arts. The organization sponsored art exhibitions and art classes and also published books written by the Yiddish language’s most accomplished authors and poets and illustrated by artists who in time became trail blazers in modernist circles.This brief flowering of Yiddish secular culture in Russia came to an end in the 1920s. As the power of the Soviet state grew under Stalin, official culture became hostile to the experimental art that the revolution had at first facilitated and even encouraged. Many artists left for Berlin, Paris and other intellectual centers. Those that remained, like El Lisitzky, ceased creating art with Jewish themes and focused their work on furthering the aims of Communism. Tragically, many of them perished in Stalin’s murderous purges.The ArtistsEliezer Lisitzky (1890–1941), better known as El Lisitzky, was a Russian Jewish artist, designer, photographer, teacher, typographer, and architect. He was one of the most important figures of the Russian avant-garde, helping develop Suprematism with his friend and mentor, Kazimir Malevich. He began his career illustrating Yiddish children\'s books in an effort to promote Jewish culture. In 1921, he became the Russian cultural ambassador in Weimar Germany, working with and influencing important figures of the Bauhaus movement. He brought significant innovation and change to the fields of typography, exhibition design, photomontage, and book design, producing critically respected works and winning international acclaim. However, as he grew more involved with creating art work for the Soviet state, he ceased creating art with Jewish themes. Among the best known Yiddish books illustrated by the artist is Sikhes Hulin by the writer and poet Moshe Broderzon and Yingel Tsingle Khvat, a children’s book of poetry by Mani Leyb. Both works have been completely digitized and can be found here.Joseph Chaikov (1888-1979) was a Russian sculptor, graphic artist, teacher, and art critic. Born in Kiev, Chaikov studied in Paris from 1910 to 1913. Returning to Russia in 1914, he became active in Jewish art circles and in 1918 was one of the founders of the Kultur-Lige in Kiev. Though primarily known as a sculptor, in his early career, he also illustrated Yiddish books, many of them children’s books. In 1921 his Yiddish book, Skulptur was published. In it, the artist formulated an avant-garde approach to sculpture and its place in a new Jewish art. It too is in the Beinecke collection.Another of the great artists from this remarkable period in Yiddish cultural history is Issachar Ber Ryback. Together with Lisistzky, he traveled as a young man in the Russian countryside studying Jewish folk life and art. Their findings made a deep impression on both men as artists and as Jews and folk art remained an aoffering influence on their work. One of Ryback’s better known works is Shtetl, Mayn Khoyever heym; a gedenknish (Shtetl, My destroyed home; A Remembrance), Berlin, 1922. In this book, also in the Beinecke collection, the artist depicts scenes of Jewish life in his shtetl (village) in Ukraine before it was destroyed in the pogroms which followed the end of World War I. Indeed, Shtetl is an elegy to that world.David Hofstein’s book of poems, Troyer (Tears), illustrated by Mark Chagall also mourns the victims of the pogroms. It was published by the Kultur-Lige in Kiev in 1922. Chagall’s art in this book is stark and minimalist in keeping with the grim subject of the poetry. Chagall was a leading force in the new emerging Yiddish secular art and many of the young modernist artists of the time came to study and paint with him in Vitebsk, his hometown. Lisistzky and Ryback were among them. Chagall, however, parted ways with them when their artistic styles and goals diverged. Chagall moved to Moscow in 1920 where he became involved with the newly created and innovative Moscow Yiddish Theater. Jews in the Russian Avant Garde: IntroductionWell, isn’t this a pickle. There was an exhibition of art by Russian Jews at the Jewish Museum in New York in 1996. Aleksandra Shatskikh wrote an article for its catalogue – in English. I can find no trace of it in the original, but as luck would have it, a translation into Russian exists. I’m hanged if I am going to translate it back into English, so I’ll just pick points of interest from it. It was about the Jewish participation in the Russian Avant Garde. Despite the name, it was not just a Russian phenomenon. Lots of nationalities of the Russian (and Soviet) empire participated in it, among them Ukrainians, Belorussians, Armenians, Finns, Poles, even Italians and Germans … and, of course, Jews.We have all heard of Marc Chagall, but he was not alone in lending a Jewish sensibility to this great movement in art. There were specific characteristics to their art that allow one to make the claim that there was indeed a Jewish Russian avant-garde. They participated fully in the development of the genre, but did so whilst seeking to discover their Jewish consciousness during a period of intense scrutiny of their identity and patriotism. The dual nature of these artists was felt throughout the history of the Russian avant-garde, which, though lasting scarcely twenty years (from the first exhibition in 1910 titled ‘Jack of Diamonds’ to the great schism of 1929), demonstrates several stages in their artistic progress.In the beginning of the 1910s, four centres of the Russian avant-garde could be identified – the native cities of St Petersburg and Moscow, and the foreign cities of Paris and Munich. There were close ties between these centres, although there were sufficient distinctions as well. The secular Jewish art was more firmly established in St Petersburg, under the instruction and aegis of Leon Bakst (who taught at a private academy of E. N. Zvantseva), who taught, among others, Chagall, Alexander Romm, Sofia Dimshitz; and at the academies of M. D. Bernstein, Ya. S. Goldblatt, S. M. Zeidenberg. It has to be said, though, that there was no nationalistic conversation permitted at these schools.The first stage of the Russian avant-garde (end of the 1900s through the 1910s) had in its ranks several Jewish artists whose Jewishness didn’t appear dominantly in their works. For example, Iosif Shkolnik’s works represent a moderate version of innovative researches into the pictorial and formal problems that were sought to be addressed by all artists of the Left. Shkolnik maintained a certain presence among the bohemian circles of the northern capital as one of the prime movers of the avant-garde association ‘Union of Youth’. Nationalistic self-awareness played no role in his creative life, nor in the fortunes of Vladimir Baranov-Rossine, Adolf Milman, or others. At the dawn of the Russian avant-garde, Jewish artists were connected to the dominant trends in the arts; the process of assimilation into academic movements of the time such as Mir Iskusstvo (World of Art) prevailed even in the first stage of development of the genre.For the majority of Jewish artists, their training had to be conducted abroad, because moving out of the Pale of Settlement to Moscow or St Petersburg was difficult. Among the impressive set of Russian Parisians, as the emigre avant-gardists were called at the time, a large proportion comprised natives of the towns and shtetls of the Pale.Among the young artists and critics of the time, specific questions on the cultures of other nationalities weren’t of serious interest, unlike in the previous decades, when much of public opinion was guided by V. V. Stasov, a great enthusiast for the revival of Jewish culture in Russia. The new guard, all Russian citizens, considered themselves Russians first, which served to dissolve in the eyes of foreign observers any and all national distinctions. A series of articles by A. V. Lunacharsky from Paris to a newspaper in Kiev, titled ‘Young Russia in Paris’ (early 1914), illustrates this sublimation of identities into Russianness: it included essays on the Jews Marc Chagall, David Shterenberg and Iosif Teper. While the work of the first two is well-known, making it easy to judge their individual approaches to the question of national identity, for the last it is more tricky: going by the remarks of a contemporary critic, the issue was a hot one for Teper. Lunacharsky himself (or Yakov Tugendhold who lived in Paris at the same time) makes no mention of any Jewish theme observable in the oeuvre of the artists before the Great War. The likes of Osip Tsadkin, Jacques Lipschitz, Hannah Orlova, Mane-Katz, Oscar Meschanikov and others all considered themselves Russian. Many were members of the Russian Academy in Paris, and in the 1920s, entered the Parisian Society of Russian Artists.In Russia, their works were exhibited at the ‘World of Art’ and ‘Jack of Diamonds’ shows, and in controversial expositions by extreme avant-gardists (‘Tail of the Donkey’, ‘Targets’, ‘№4′). Marc Chagall, Nathan Altman, Leon Zack, Adolf Milman, and other Russian Parisians occupied a prominent place in the national artistic life, and were closely connected with the activities of radical artists. Meanwhile, they participated in French and international exhibitions as Russian artists; only later did many of them become masters of the modern Jewish art. They continued to consider themselves Russian, and when they set up the 1928 Exhibition of Contemporary French Art in Moscow, they included their own pieces in the Russian section. Besides the names mentioned above, we encounter others such as Mikhail Kikoin, Zachary Rybak (Issachar Ryback), Pavel Kremny.The nucleus of Russian artistic life in Paris from the beginning of the 1910s was at the Beehive (La Ruche). Here Chagall worked, as did the likes of Nathan Altman, Iosif Chaikoff, Lazar Lissitsky, David Shterenberg, all of whom involved themselves in intensive discussion and quest for the roots of Jewish identity and art. Significantly, many of these artists, whose Jewish self-identification evolved in Paris, found fertile ground for advancement when they returned to Russia. For at the same time, all Slavic peoples living in Eastern Europe were consumed with their own rising nationalistic consciousness. The Ashkenazim were no different.Whereas European artists were not so tied to their nationalistic roots, in Russia, an appeal to an artist’s national cultural heritage was a significant feature. Leftwing Russian artists claimed that they were committed to the East and drew attention to their national arts. They protest, they said, against a slavish subordination to the West. Young Jewish artists could with conviction subscribe to the same words.The likes of Kandinsky and Larionov and Malevich sought inspiration in the ancient Russian iconography and primitive art of centuries past by authors unknown, and their own works were fuelled by this investigation. Likewise, the revival of the Russian Jewry in the 19th century led young Jewish artists to the delighted rediscovery and promotion of their own heritage, which then served to propel the next stage in the creative revolution of the Jewish avant-garde.

1934 Yiddish BOOK Judaica CHAIKOV Jewish AVANT GARDE ART Russian KULTUR LIGE:

$135.00