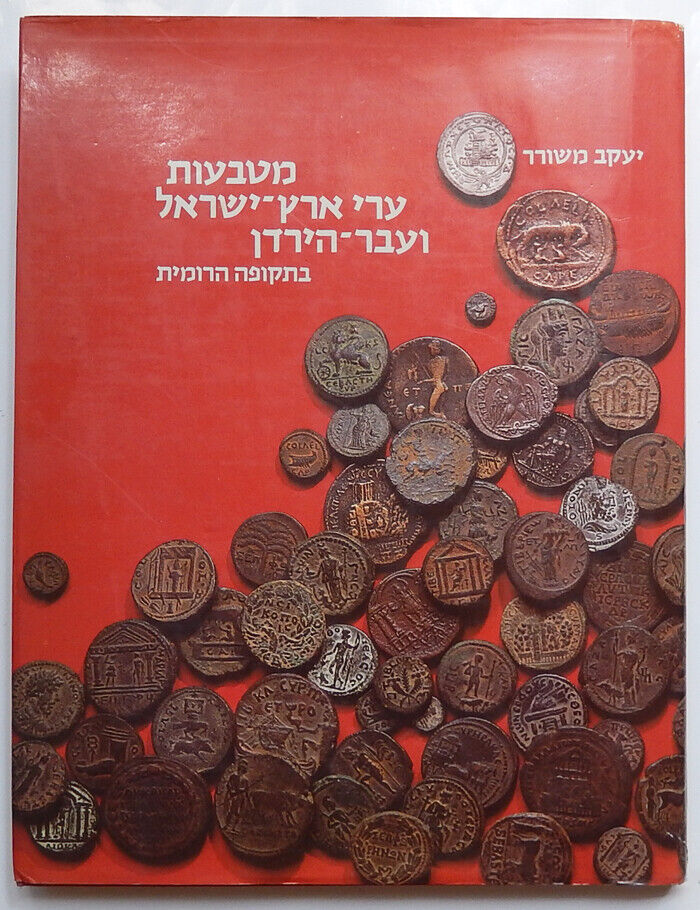

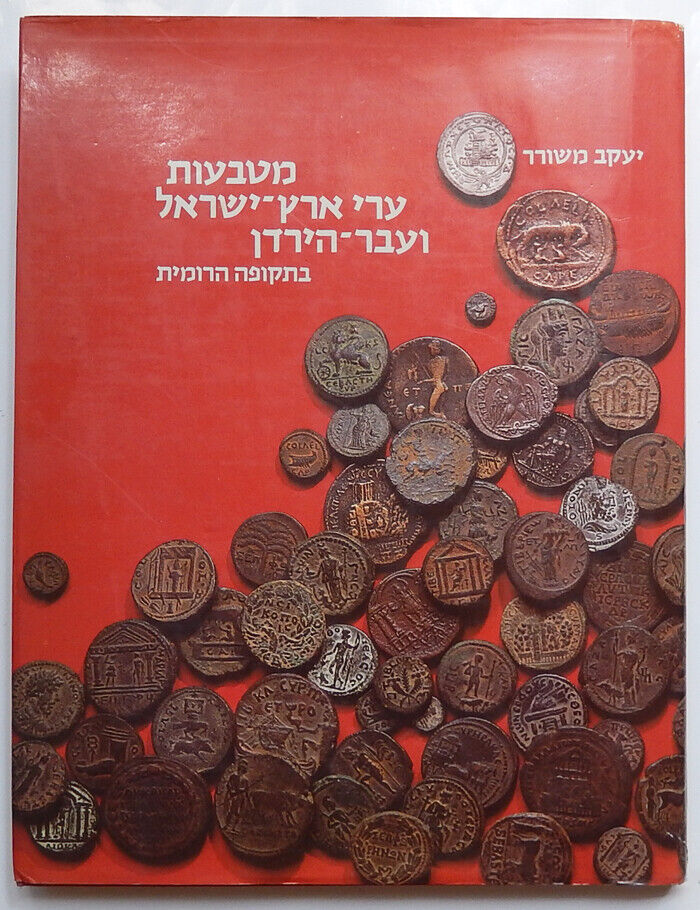

CITY COINS OF ERETZ ISRAEL & DECAPOLIS IN THE ROMAN PERIOD BOOK MESHORER 1984

When you click on links to various merchants on this site and make a purchase, this can result in this site earning a commission. Affiliate programs and affiliations include, but are not limited to, the eBay Partner Network.

CITY COINS OF ERETZ ISRAEL & DECAPOLIS IN THE ROMAN PERIOD BOOK MESHORER 1984:

$110.00

City Coins of Eretz-Israel and the Decapolis in the Roman Period

This scarce book \"City Coins of Eretz-Israel and the Decapolis in the Roman Period\", was written by Yaakov Meshorer.Published by Israel Museum, printed in Jerusalem in 1984. Great research work done by Professor Meshorer accompanied with many photos.Excellent condition. Hardcover with original dust jacket. The book contains map and photos. Size: 11.5x9 inch.

Winning buyer pays $18.00 Postage international registered air mail.

Payment option: Paypal

Authenticity 100% Guaranteed

Please have a look at my other listingsGood the first century, the Roman Empire granted many of the cities in its provinces the right to mint bronze coins. Silver coins were only minted in a few important cities outside of Rome. Coins were issued in Judaea/Palestine by 38 different cities, according to Meshorer, as follows (from North to South):Coastal Cities: Ptolemais (Akko), Dora (Dor), Caesarea, Joppa (Yafo), Ascalon (Ashkelon), Gaza, Anthedon, RaphiaInland Cities: Tiberias, Sepphoris (Sippori), Gaba, Nysa-Scythopolis, Samaria (Shomron-Sebaste), Neapolis (Shechem), Antipatris, Diospolis (Lod), Nicopolis (Emmaus), Aelia Capitolina (Jerusalem), Eleutheropolis (Beth Govrin)Cities of Transjordan: Panias, Philippopolis, Hippos (Susita), Canatha (Kenath), Abilla (Abel), Gadara (Gader), Adraa, Capitolias (Beth Reisha), Bostra (Beser), Dium, Pella (Pehal), Gerasa (Geresh), Philadelphia (Rabbat Ammon), Esbus (Heshbon), Medeba, Rabbath-Moba (Rabbath Moab), Charach-Moba (Kir Moab), Petra (Reqem)The definition of “Palestinian” cities is somewhat subjective. The British Museum Catalog of Palestine coins tallies 16 cities in Galilee, Samaria and Judaea; Klimowsky lists 32 cities under the heading “Palestine;” and Rosenberger enumerates 22 cities in “Palestine” and 18 in “

Eastern Palestine.”While a scattering of city coins were minted earlier, the time of the First Revolt (66-70 CE) saw the initial pronounced production of city coins in Judaea ... and the number of mints blossomed after the defeat of the Jews in the Second Revolt (132-135 CE). The Ascalon Mint deserves special mention, since it produced coins almost continuously from about 375 BCE through 235 CE; one of its more interesting issues features the famous Cleopatra on a silver shekel.Some historic coins - issued by Akko-Ptolemais, Aelia Capitolina- Jerusalem, Caesarea, etc. -- picture the Roman ceremonial founding of the city. The Emperor is shown in a cart pulled by a bull and ox, defining the boundary as the area enclosed by a plough in 24 hours.Coins of Judaea and Palestine are also presented in our Judean and Biblical catalog section. Here all coins of Roman Judaea and Palestine are grouped together and listed from highest price to lowest. In our Judean and Biblical catalog section coins are organized by types and rulers and are presented with additional historical information and biblical references.Copper Hendin 1169, Meshorer AJC 1a, MCP O-I-04, Fontanille Celator Feb \'05 O2/R3, HGC 10 651, VF, areas not fully struck, nice green patina highlighted by buff earthen fill, weight 10.14 g, maximum diameter 28.0 mm, die axis 0o, Samaria mint, 40 - 37 B.C.; obverse HPΩ∆OY BAΣIΛEΩΣ (Greek: of King Herod) in 3 strait lines, tripod, ceremonial bowl (lebes) above, LΓ - P (year 3 of the tetrarchy = 40 B.C.) across fields; reverse military helmet facing with cheek pieces and straps, wreathed with acanthus leaves, fillets and star above, flanked by two palm-branches;he Bible does not tell the date of the Crucifixion, but based on Biblical clues, the Jewish calendar and astronomical evidence many scholars believe it was Friday, April 3, 33 A.D. John the Baptist began his ministry in 28 or 29 A.D. and the Gospel of John points to three separate

Passovers during Jesus\' ministry. Jesus was executed on the orders of Pontius Pilate, the Roman prefect of Judaea from 26 to 36 A.D. This limits the years to between 30 and 36 A.D. John P. Meier\'s, A Marginal Jew, cites 7 April 30 A.D., 3 April 33 A.D., and 30 March 36 A.D. as astronomically possible Friday Nisan 14 dates during this period. Isaac Newton, using the crescent of the moon, determined the year was 34 A.D. but John Pratt argued that Newton made a minor computation error and 33 A.D. was the accurate answer using Newton\'s method. Using similar computations, in 1990 astronomer Bradley Schaefer arrived at Friday, April 3, 33 A.D. A third method, using a completely different astronomical approachAelia Capitolina (Traditional English Pronunciation: /ˈiːliə ˌkæpɪtəˈlaɪnə/; Latin in full: COLONIA AELIA CAPITOLINA) was a Roman colony founded by Emperor Hadrian in Jerusalem, which had been almost totally razed after the siege of 70 AD, during his trip to Judah in 129/130 AD.[1][2] The foundation of Aelia Capitolina and the construction of a temple to Jupiter at the site of the former temple may have been one of the causes for the outbreak of the Bar Kokhba revolt in 132 AD.[2][3] Aelia Capitolina remained as the official name until Late Antiquity and the Aelia part of the name transliterated toccording to Eusebius, the Jerusalem church was scattered twice, in 70 and 135, with the difference that from 70–130 the bishops of Jerusalem have evidently Jewish names, whereas after 135 the bishops of Aelia Capitolina appear to be Greeks.[4] Eusebius\' evidence for continuation of a church at Aelia Capitolina is confirmed by the Bordeaux Pilgrim.[5]The Roman emperor Hadrian decided to rebuild the city as a Roman colony, which would be inhabited by his legionaries.[6] Hadrian\'s new city was to be dedicated to himself and certain Roman gods, in particular Jupiter.[7]There is controversy as to whether Hadrian\'s anti-Jewish decrees followed the Jewish Bar Kokhba revolt or preceded it and were the cause of the revolt.[8] The older view is that the Bar Kokhba revolt, which took the Romans three years to suppress, enraged Hadrian, and he became determined to erase Judaism from the province. Circumcision was forofferden and Jews were expelled from the city. Hadrian renamed Iudaea Province to Syria Palaestina, dispensing with the name of Judaea.[9]Jerusalem was renamed \"Aelia Capitolina\"[10] and rebuilt in the style of a typical Roman town. Jews were prohibited from entering the city on pain of death, except for one day each year, during the holiday of Tisha B\'Av. Taken together, these measures[11][12][13] (which also affected Jewish Christians)[14] essentially secularized the city.[15] The ban was maintained until the 7th century,[16] though Christians would soon be granted an exemption: during the 4th century, the Roman Emperor Constantine I ordered the construction of Christian holy sites in the city, including the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. Burial remains from the Byzantine period are exclusively Christian, suggesting that the population of Jerusalem in Byzantine times probably consisted only of Christians.[17]Laureate Head of Titus to right, surrounded by Latin inscription: VIIIReverse: Mourning woman beside a palm tree (personification of Judea) beside Titus, surrounded by Latin inscription: IVDAEA CAPTA, and inscription on exergue: S CCaesarea, Hebrew H̱orbat Qesari, (“Ruins of Caesarea”), ancient port and administrative city of Palestine, on the Mediterranean coast of present-day Israel south of Haifa. It is often referred to as Caesarea Palaestinae, or Caesarea Maritima, to distinguish it from Caesarea Philippi near the headwaters of the Jordan River. Originally an ancient Phoenician settlement known as Straton’s (Strato’s) Tower, it was rebuilt and enlarged in 22–10 BCE by Herod the Great, king of Judaea under the Romans, and renamed for his patron, the emperor Caesar Augustus. It served as a port for Herod’s newly built city at Sebaste (Greek: Augusta), the ancient Samaria of central Palestine. Caesarea had an artificial harbour of large concrete blocks and typical Hellenistic-Roman public buildings. An aqueduct brought water from springs located almost 10 miles (16 km) to the northeast. Caesarea served as a base for the Herodian navy, which operated in aid of the Romans as far as the Black Sea.The city became the capital of the Roman province of Judaea in 6 CE. Subsequently, it was an important centre of early Christianity; in the New Testament it is mentioned in Acts in connection with Peter, Philip the Apostle, and, especially, Paul, who was imprisoned there before being sent to Rome for trial. According to the 1st-century-CE historian Flavius Josephus, the Jewish revolt against Rome, which culminated in the destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple in 70 CE, was touched off by an incident at Caesarea in 66 CE. During the Bar Kokhba revolt of 132–135 CE, the Romans tortured and killed the 10 greatest leaders and sages of Palestinian Jewry, including Rabbi Akiba. Caesarea was almost certainly the place of execution of Rabbi Akiba and the others according to tradition (c. 135 CE). The death of these Ten Martyrs is still commemorated in the liturgy for Yom Kippur (the Day of Atonement).Coins and their cities : architecture on the ancient coins of Greece, Rome greekThe Roman province of Judea (/dʒuːˈdiːə/; Hebrew: יהודה, Standard Yəhūda Tiberian Yehūḏā; Greek: Ἰουδαία Ioudaia; Latin: Iūdaea), sometimes spelled in its original Latin forms of Iudæa or Iudaea to distinguish it from the geographical region of Judea, incorporated the regions of Judea, Samaria and Idumea, and extended over parts of the former regions of the Hasmonean and Herodian kingdoms of Judea. It was named after Herod Archelaus\'s Tetrarchy of Judea, but the Roman province encompassed a much larger territory. The name \"Judea\" was derived from the Kingdom of Judah of the 6th century BCE.Following the deposition of Herod Archelaus in 6 CE, Judea came under direct Roman rule,[1] during which time the Roman procurator was given authority to punish by execution. The general population also began to be taxed by Rome.[2] The province of Judea was the scene of unrest at its founding in 6 CE during the Census of Quirinius, the crucifixion of Jesus circa 30–33 CE, and several wars, known as the Jewish–Roman wars, were fought during its existence. The Second Temple of Jerusalem was destroyed by the Romans in 70 CE near the end of the First Jewish–Roman War, and the Fiscus Judaicus was instituted. After the Bar Kokhba revolt (132–135), the Roman Emperor Hadrian changed the name of the province to Syria Palaestina and the name of the city of Jerusalem to Aelia Capitolina, which certain scholars conclude was an attempt to disconnect the Jewish people from their homeland.[3][4]BackgroundPompey in the Temple of Jerusalem, by Jean FouquetPompey in the Temple of Jerusalem, by Jean FouquetThe first intervention of Rome in the region dates from 63 BCE, following the end of the Third Mithridatic War, when Rome established the province of Syria. After the defeat of Mithridates VI of Pontus, Pompey sacked Jerusalem and installed Hasmonean prince Hyrcanus II as Ethnarch and High Priest but not as king. Some years later Julius Caesar appointed Antipater the Idumaean, also known as Antipas, as the first Roman Procurator. Antipater\'s son Herod was designated \"King of the Jews\" by the Roman Senate in 40 BCE[5] but he did not gain military control until 37 BCE. During his reign the last representatives of the Hasmoneans were eliminated, and the huge port of Caesarea Maritima was built.[6]Herod died in 4 BCE, and his kingdom was divided among three of his sons, two of whom (Philip and Herod Antipas) became tetrarchs (\'rulers of a quarter part\'). The third son, Archelaus, became an ethnarch and ruled over half of his father\'s kingdom.[7] One of these principalities was Judea, corresponding to the territory of the historic Judea, plus Samaria and Idumea.Archelaus ruled Judea so badly that he was dismissed in 6 CE by the Roman emperor Augustus, after an appeal from his own population. Herod Antipas, ruler of Galilee and Perea from 4 BCE was in 39 CE dismissed by Emperor Caligula. Herod\'s son Philip ruled the north

Eastern part of his father\'s kingdom.[8]Judea as Roman province(s)The Roman empire in the time of Hadrian (ruled 117–138 CE), showing, in western Asia, the Roman province of Judea. 1 legion deployed in 125.The Roman empire in the time of Hadrian (ruled 117–138 CE), showing, in western Asia, the Roman province of Judea. 1 legion deployed in 125.Part of a series on theHistory of PalestinePrehistoryNatufian historyCanaanPhoeniciaAncient Israel and JudahPhilistiaMedian EmpireClassical periodSeleucusAntigonusHasmonean dynastyHerodian kingdomProvince of JudeaSyria PalaestinaByzantine Empire(Palaestina Prima / Secunda)Islamic ruleMuslim conquestRashidun (Jund Filastin, Jund eraMandatory PalestineAll-PalestineJordanian West BankEgyptian Gaza StripIsraelMilitary GovernorateIsraeli Civil AdministrationPalestinian Authority (West Bank bantustans; Gaza Strip)State of PalestinePalestine portalvtePart of a series on theHistory of IsraelAncient Israel and JudahPrehistory NatufianCanaanIsraelitesUnited monarchyNorthern KingdomKingdom of JudahBabylonian ruleSecond Temple period (530 BCE–70 CE)Persian ruleHellenistic periodHasmonean dynastyHerodian dynasty KingdomTetrarchyRoman JudeaLate Classic (70-636)Roman PalaestinaByzantine Palaestina PrimaSecundaMiddle Ages (636–1517)Caliphates FilastinUrdunnKingdom of JerusalemAyyuoffer dynastyMamluk SultanateModern history (1517–1948)Ottoman rule EyaletMutasarrifateOld YishuvZionismOETABritish mandate YishuvState of Israel (1948–present)Timeline YearsIndependenceArab–Israeli conflictAusteritySilicon WadiIran–Israel conflictHistory of the Land of Israel by topicHistorical mapsHistorical populationHistorical literatureJudaismJerusalemZionismJewish leadersJewish warfareRelatedJewish historyHebrew calendarArchaeologyMuseumsIsrael portalvteUnder a prefect (6–41)In 6 CE Archelaus\' tetrachy (Judea, plus Samaria and Idumea)[9] came under direct Roman administration. The Judean province did not initially include Galilee, Gaulanitis (today\'s Golan), nor Peraea or the Decapolis. Its revenue was of little importance to the Roman treasury, but it controlled the land and coastal sea routes to the \"bread basket\" of Egypt and was a buffer against the Parthian Empire. The capital was at Caesarea Maritima,[10] not Jerusalem. Quirinius became Legate (Governor) of Syria and conducted the first Roman tax census of Syria and Judea, which was opposed by the Zealots.[11] Judea was not a senatorial province, nor an imperial province, but instead was a \"satellite of Syria\"[12] governed by a prefect who was a knight of the Equestrian Order (as was that of Roman Egypt), not a former consul or praetor of senatorial rank.[13]Autonomy under Herod Agrippa (41–44)Between 41 and 44 CE, Judea regained its nominal autonomy, when Herod Agrippa was made King of the Jews by the emperor Claudius, thus in a sense restoring the Herodian dynasty, although there is no indication that Judea ceased to be a Roman province simply because it no longer had a prefect. Claudius had decided to allow, across the empire, procurators, who had been personal agents to the Emperor often serving as provincial tax and finance ministers, to be elevated to governing magistrates with full state authority to keep the peace. He may have elevated Judea\'s procurator to imperial governing status because the imperial legate of Syria was not sympathetic to the Judeans.[17]A fiscal procurator (procurator Augusti) was the chief financial officer of a province during the Principate (30 BC – AD 284). A fiscal procurator worked alongside the legatus Augusti pro praetore (imperial governor) of his province but was not subordinate to him, reporting directly to the emperor. The governor headed the civil and judicial administration of the province and was the commander-in-chief of all military units deployed there. The procurator, with his own staff and agents, was in charge of the province\'s financial affairs, including the following primary responsibilities:[3]the collection of taxes, especially the land tax (tributum soli), poll tax (tributum capitis), and the portorium, an imperial duty on the carriage of goods on public highwayscollection of rents on land belonging to imperial estatesmanagement of mines[4]the distribution of pay to public servants (mostly in the military)The office of fiscal procurator was always held by an equestrian, unlike the office of governor, which was reserved for members of the higher senatorial order.[5] The reason for the dual administrative structure was to prevent excessive concentration of power in the hands of the governor, as well as to limit his opportunities for peculation. It was not unknown for friction to arise between governors and procurators over matters of jurisdiction and financeCoponius 6–9 C.E.Marcus Ambibulus 9–12 C.E.Rufus Tineus 12–15 C.E.Valerius Gratus 15–26 C.E.Pontius Pilate 26–36 C.E.Marcellus 36–37 C.E.Marullus 37–41 C.E.Cuspius Fadus 44–46 C.E.Tiberius Julius Alexander 46–48 C.E.Ventidius Cumanus 48–52 C.E.Antonius Felix 52–60 C.E.Porcius Festus 60–62 C.E.Albinus 62–64 C.E.Gessius Florus 64–66 C.E.itle of the governors (first over Judea, later over most of Palestine) appointed by Rome during the years 6–41 and 44–66 C.E. From a recently discovered inscription in which *Pontius Pilate is mentioned, it appears that the title of the governors of Judea was also praefectus. Procuratorial rule came into force with the banishment of *Herod \'s son *Archelaus in the year 6 and was interrupted for three years during the reign of *Agrippa I (41–44). The Judean-Palestinian procurator held the power of jurisdiction with regard to capital punishment (jus gladii). Roman citizens had the privilege of provocatio, i.e., the right to transfer the trial from the provincial governor to the emperor (cf. the case of *Paul , Acts 25:10–12; cf. 22:25ff.). The procurator was subject to the Roman legate in Syria, an illustration of this being the deportation of Pontius Pilate (26–36 C.E.) by Vitellius. Josephus also states (Wars, 2:280–1) that formal charges would have been preferred by the Jews against the last procurator Gessius *Florus (64–66 C.E.; see below) but that they refrained from taking their case to *Gallus in Syria from fear of reprisals. The Sanhedrin was allowed to exercise jurisdiction in civil matters, although the procurators could exercise control in this sphere as well. As a rule, the procurators maintained supervision over the country from their official residence at Caesarea. On Jewish festivals, their seat was temporarily transferred to Jerusalem in order to control the thousands who flocked to the Temple and on these occasions they sometimes gave physical expression to their hatred of Rome.It is fair to assert that the procurators were either openly hostile or, at best, indifferent to the needs of the Jewish populace. They were notorious for their rapacity. Their relatively short tenure, coupled with hostility toward Jews as a whole, may have impelled them to amass quick profits. Whatever the case, the last two procurators before the Jewish War (66 C.E.), *Albinus and Gessius Florus, as a consequence of their monetary extortions and generally provocative acts, were indubitably instrumental in hastening the outbreak of hostilities. The only exception appears to have been Porcius *Festus (60–62 C.E.) who made vain attempts to improve conditions. The procuratorial administration made an unfortunate beginning when the very first procurator, *Coponius , was dispatched to govern Judea, while the Syrian legate *Quirinius carried out a census (Jos., Ant., 18:1). The political consequences of this act were not delayed, as it led to the establishment of the Fourth Philosophy ( *Sicarii ) by *Judah the Galilean and the Pharisee Zadok. *Valerius Gratus (15–26) went so far as to depose high priests at will, an outrage on popular feeling hitherto perpetrated only by Herod. The outraged feelings of the populace were not calmed with the appointment of Gratus\' successor, Pontius Pilate, during whose term of office Jesus was crucified. Pilate\'s decision to introduce into the city military standards bearing the emperor\'s likeness may have been inspired by Rome. Incontrovertible, however, are his own acts of cruelty and his miscarriages of justice, such as the execution of Galilean patriots without trial and his violence toward the Samaritans (35 C.E.). The latter act caused his recall to Rome and deposition by Vitellius in the spring of 36. So serious were the possible consequences of his misrule in the eyes of Rome that Vitellius was specially charged with the task of regaining Jewish favor by granting minor concessions.While the \"second series\" of procurators, after the interlude of semi-independence under Herod Agrippa I, were deprived of the power of appointing the high priest, the very first of them, Cuspius *Fadus , gained custody of the priestly vestments. Although appointed by Claudius to counteract the Syrian legate\'s antipathy toward the Jews, Fadus adopted violent means in suppressing the followers of the pseudo-Messiah *Theudas . Tiberius *Alexander ordered the execution of Jacob and Simeon, sons of Judah the Galilean. Ventidius *Cumanus , next in office, not only let his troops cause a panic in the overcrowded Temple area on

Passover, resulting in the death of 20,000 Jews (Jos., Ant., 20:105–12) but in addition armed the Samaritans against them. Whether the measure was actually considered necessary in order to maintain order is unclear. Cumanus was, however, subsequently removed by the Syrian legate. The last of the Judean procurators, Gessius Florus (see above), is reported by Josephus to have sparked off the Jewish War with his demand for 17 talents from the Temple funds, which caused rioting leading up to the outbreak of hostilities on a large scale. After 70 C.E. the office of procurator sometimes alternated with that of legate and was subordinate to the governor of the region, eventually being disbanded altogether.

CITY COINS OF ERETZ ISRAEL & DECAPOLIS IN THE ROMAN PERIOD BOOK MESHORER 1984:

$110.00