1957 Sedder ISRAEL INDEPENDENCE HAGGADAH English PHOTO BOOK Jewish JUDAICA

When you click on links to various merchants on this site and make a purchase, this can result in this site earning a commission. Affiliate programs and affiliations include, but are not limited to, the eBay Partner Network.

1957 Sedder ISRAEL INDEPENDENCE HAGGADAH English PHOTO BOOK Jewish JUDAICA:

$85.00

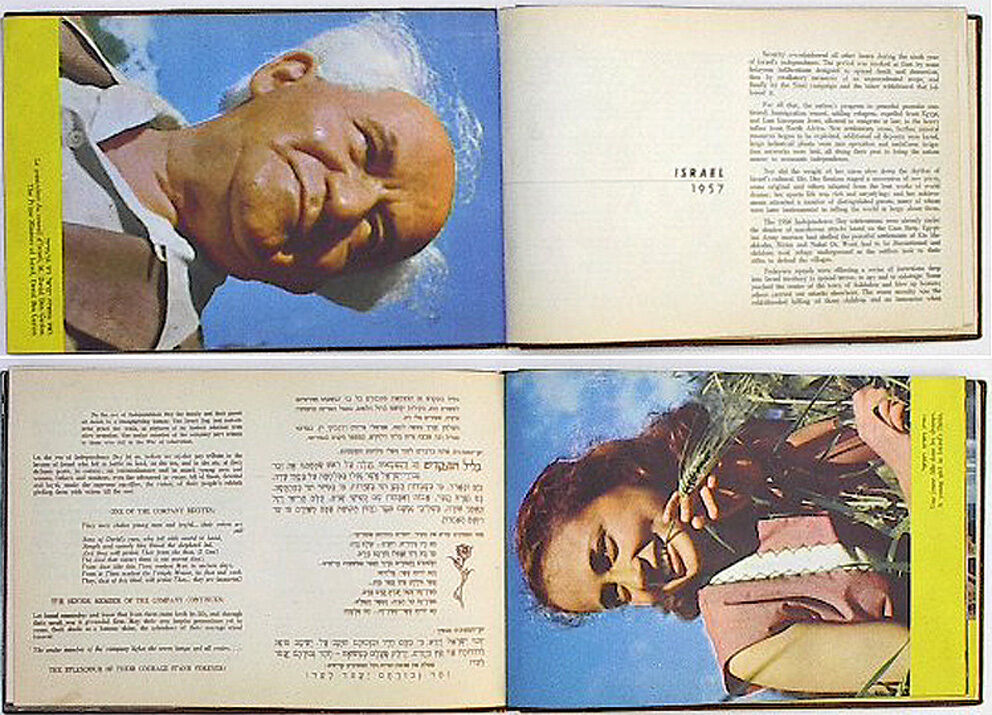

DESCRIPTION : Here for sale is a quite RARE edition of\"HAGGADAH For The DAY OF INDEPENDENCE \" which was published in 1957 ,One of only a few attempts to create such INDEPENDENCE HAGGADAH , Attemptswhich didn\'t bring much fruits untill nowdays . The HAGGADAH was written byAvraham Ben Shushan and it is partly based on the legendary INDEPENDENCEHAGGADAH by Ahaton Meged , The one which he wrote for ZAHAL , The IDF , Only 4years sooner. Full ENGLISH translation to the HAGGADAH TEXT and all theheadings of the NUMEROUS accompanied PHOTOS. HC . 6.5 x 9.5\" . Unpaginated. Good condition. Used. ( Pls look at scan for accurate AS IS images ) Will be sent inside a protective rigid envelope .

PAYMENTS : Payment method accepted : Paypal .SHIPPMENT : SHIPP worldwide via registered airmailis $ 17 . Book will be sent inside a protective envelope . Handling within 3-5 days after payment. Estimated duration 14 days. The Passover Haggadah and the Haggadah of Yom Ha\'Atzma\'ut Asa Kasher \"The great Hebrew holiday.\" The first Yom Ha\'Atzama\'ut was received with those words in the address delivered by the chairman of the \"First Knesset of Israel, meeting on the first anniversary of Israel\'s independence, greeting the dear Hebrew holiday.\"Yosef Sprintzak described Yom Ha\'Atzma\'ut with phrases such as \"the new Hebrew holiday\" because they seemed appropriate to people of his day. Two words always reappear in those descriptions, and they are both deep and fascinating. However, it seems that they have lost their significance with the passing years.One word, ha\'ivri [\"the Hebrew\"] has fallen out of common usage because its sense has split into several different meanings: \"the Jewish,\" \"the Israeli,\" and so forth. This reflects an interesting and important historical process, but this is not the place to deal with it.The other word, hag [\"holiday\"], is still commonly used in reference to Yom Ha\'Atzma\'ut, but it does not serve as a living and accurate description, but rather as a \"frozen\" expression. Usually, Yom Ha\'Atzma\'ut is celebrated as a vacation, a time for relaxation or entertainment, rather than as a holiday marked by joy or activities informed by some special spirit of the day. This reflects an interesting an important cultural process, which I shall presently address.It is self-evident that not every special day is a holiday. A memorial day is not a holiday. It is less obvious that even a special day involving more joy than sorrow can also fail to meet the definition of a holiday. Such, for instance, is the 18th of Iyyar, known as La\'G Ba\'Omer. One tradition connects it with the outbreak of the Great Revolt, a second tradition claims that it marks the end of a great plague, while a third associates it with R. Shimon bar Yohai. Everyone who is loyal to these traditions experiences the day as a point of transition from a period of mourning to one of joy, but it is not considered to be a holiday.(I could not find the expression Hag Lag Ba\'Omer in any culturally significant text, with the exception of a few children\'s songs: Levin Kipnis\'s Kashteinu al K\'teifeinu (written in 1921), includes the line \"It is the holiday of Lag Ba\'omer for us [hag lag ba\'omer lanu], a joy for a girl and a boy.\" Ora Morag\'s Heitz va\'Keshet (1979) opens with the words, \"On the holiday of Lag Ba\'Omer, I was told by Tomer.\")The State of Israel established Yom Ha\'Atzma\'ut as a holiday. Here is how the law from the year 5709 puts it: \"The Knesset hereby proclaims that the day of the 5th of Iyyar is Yom Ha\'Atzma\'ut which shall be celebrated every year as a state holiday.\" It is not difficult to understand why the members of the first Kenesset saw fit to celebrate the day of the proclamation of the state\'s founding as a holiday. All of them belonged to a world in which Yom Ha\'Atzma\'ut marked the historical transition from being a people living under foreign rule - be it in the Diaspora or in the Land of Israel - to being a nation \"that exists independently in its own sovereign state,\" to quote from Israel\'s Declaration of Independence. The significance of this transition is so deep, so pervasive, so jarring, that it is appropriate for it to be marked by a holiday.Yom Ha\'Atzma\'ut is a natural holiday for a Jew who lived through this transition, even more so for a Jew who participated in the struggle to bring about the transition. Such people find the joy of national independence inside themselves because they had \"left Egypt\" themselves. I recall myself as a wee ear-witness, listening to the broadcast of the ceremony proclaiming the establishment of the state. I remember the strains of Hatikva rising up from our radio for the first time in the State of Israel. Even today, every time I sing the anthem or hear it sung at a ceremony, I am flushed with emotion as I recall the first time it was sung in an independent Israel.So it is for a Jew who witnessed the establishment of the political independence of the Jewish People. So it is for someone like myself, who experienced it as a small child. But what of those who were born here at that time? And what of those who were born here a decade later, or twenty years later, or on the state\'s fiftieth anniversary? It would seem that the stirring voice of the establishment of our independence cannot echo naturally or automatically in their hearts, for they were born into independence, they grew up as children of independence, they came into their own as the sons and daughters of \"a free people in our land, the land of Zion and Jerusalem.\" (In the original version of Imbar\'s Hatikva, the \"ancient hope\" is \"return to the land of our fathers, to the city where David encamped.\" It is not hard to notice the crucial difference between dwelling in our father\'s land and being a free nation in our land.) Independence is the landscape of their birthplace. The establishment of independence is a story passed down in the family or read from the pages of history books. That is why, in their world, Yom Ha\'Atzama\'ut can be a day of celebrations, but it cannot be a genuine holiday.Nonetheless, one whose cultural world has roots in the Jewish tradition will be greatly surprised by how rapidly the perception of Yom Ha\'Atzma\'ut as \"the State\'s holiday\" has degenerated. From the standpoint of that tradition, the exodus from Egypt was a single ancient event, but we still find \"a commemoration of the exodus from Egypt\" in the formulation of the Kiddush every Sabbath eve. Every Seder night we learn that, in the Haggadah\'s words, \"in each and every generation, one is required to see himself as if he had left Egypt.\" Two thousand years after the event, the Passover Haggadah invites us to reenact the exodus for ourselves. It would seem that one may fulfill this obligation by trying to identify with our fathers and mothers, the original people who left Egypt as they were in themselves. However, it seems preferable to bring the exodus to us rather than to bring ourselves to the exodus. In order to \"see himself as if he had left Egypt,\" one must identify his own present \"Egypt\" and commit himself to leave it in the future. To my mind, this \"Egypt\" is idolatry, understood in its broadest and deepest sense, but I shall not dwell upon that here. (I have written on it at length in my Yahadut ve\'Elilut, Misrad ha\'Bitchon - Hotza\'a la\'Or, Tel-Aviv 2004.) Yom Ha\'atzma\'ut could have remained a genuine holiday for the generations if it had developed a similar tradition in a parallel spirit: \"In each and every year, one is required to see himself as if he had been in Israel on the day of its establishment.\" If such a tradition had developed naturally it would have created the means by which one could fulfill the obligation to see himself as if he had been present in Israel at the moment of its founding. An idea known to us from alternative version of the Haggadah\'s text could have offered a starting point: \"In each and every generation, one is required to show himself as if he had left Egypt.\" (This is the formulation found in Yemenite Haggadahs and in several of the older printed editions. See my grandfather HaRav Menachem Mendel Kasher\'s Haggadah Sheleima, Jerusalem 5721, pg. 64.) How does one fulfill his obligation \"to show himself\"? The basic answer offered to us by the Jewish tradition is to do so by means of ceremonies and texts. There is no holiday without its own particular ceremonies and there is no holiday lacking its own particular texts to be read. Take note: this is not a matter of a ceremony carried out by the High Priest, but rather, of a ceremony in which every individual person takes part. We are not referring to texts sung by the Levites in the Temple, but of texts that every individual is to recite together with the other participants. Such is the holiday of Passover and such is the holiday of Sukkot in the Jewish tradition. Such can be the holiday of Atzma\'ut.This is the place to recall the question asked by the son, while the section beginning \"The Torah spoke of four sons\" stands in the background. It is one of the foundational elements that shaped the entire Haggadah: When your son asks you tomorrow, saying: \"What are the testaments and the laws and the ordinances?\" (Devarim 6:20). On Passover, the answer is already prepared, waiting for us in the Haggadah. If Yom Ha\'Atzma\'ut were a real holiday, a prepared answer would also have to be waiting for us: the significance of the ceremony is such and such, and everyone should say it aloud.Part of the possible answer is obvious. The Seder night expresses the importance and significance of the exodus from Egypt, so that one will honor that which possesses such importance and organize his life by the light of that which bears such importance. Similarly, Hag Ha\'Atzma\'ut can express the importance and significance of the political independence of the Jewish People in its historical homeland, in order to honor that which bears such importance and in order that one shape one\'s life by the light of that which bears such significance.Another part of the answer, which is especially appropriate for our generations, is not immediately obvious.We are used to saying that the State of Israel was founded on the 5th of Iyyar, 5708. Thus, the precise title of the \"Declaration of Independence\" is the \"Declaration of the Founding of the State of Israel.\" On that day, the State of Israel was founded as a political and legal entity, but the process of founding the State of Israel in the broadest sense of that historical expression began on that day but has yet to be completed. We have not finished founding our state. We have not finished removing the Jewish People from exile, and we have yet to remove the exile from within the Jewish people. We have not finished establishing the inner relationships of the state, including its identity and constitution, and we have yet to finish establishing the state\'s external relations, particularly those involving the neighboring nation. As a result, each of us can still play a part in the historical process of state building. Each of us can still shoulder responsibility for a part of this stirring process. Hag Ha\'Atzma\'ut can also express that idea through ceremonies and texts. A little before the State of Israel\'s first birthday, the Knesset discussed a proposal by Israel\'s first government concerning \"the Sovereignty Day Law.\" The first minister of education and culture, M.K. Zalman Shazar (who was later to become the third president) suggested that the day of Yom Ha\'Atzma\'ut should be determined by the Hebrew calendar. M.K. Prof. Ben-Zion Dinur (who would later serve as minister of education and culture in four governments), presented four elements that appear in each of Israel\'s holidays: historical memory, the \"idea,\" the symbol, and the \"organicness\" - which refers to the natural connection between the holiday and its particular historical memory and idea.Dinur suggested that the historical memory be that of the victory in the War of Independence, that the idea be sovereignty, and that the symbol be the Flag. One can question the details of these proposals, but here we shall only consider the fourth element, the \"organicness,\" in the broad sense of the day\'s connection to history as the idea of political independence is expressed within the course of history, \"to be like every other nation, existing autonomously in its own sovereign state\" - both in periods in which that goal was an object of longing and struggle as well as in times of further development after sovereignty was already established.I believe that there is only one way to make Yom Ha\'Atzma\'ut into a genuine holiday, a holiday that will merge naturally into the history of the Jewish People as a nation which is \"autonomous\" in every important aspect of is existence. That is the way of ceremonies and texts that bear a clear relationship to the Passover Haggadah which is known to us from the Seder night. The notion of creating an \"Independence Haggadah\" along the lines of the Passover Haggadah offers three advantages. First; although that by its very nature, any such Haggadah for Yom Ha\'Atzma\'ut is bound to contain significantly novel material in central sections of its content, its strong connections to the Passover Haggadah will immediately invest it with deep historical roots. The Haggadah for Yom Ha\'Atzma\'ut will be a new text possessing ancient roots. Far from involving paradox, this will represent a unique cultural achievement. Second, the employment of texts will constitute a natural element of similarity between the Passover Haggadah and a reasonable Yom Ha\'Atzma\'ut Haggadah. Just as the Passover Haggadah is the foundational text of a ceremony, so too the Yom Ha\'Atzma\'ut Haggadah can be a text designated for a ceremony, be it in the format of the Seder night or in some other format - on the night following Yom Ha\'Atzma\'ut, for instance. Third, the main characteristics of the texts will constitute a natural element of difference between the Passover Haggadah and a reasonable Yom Ha\'Atzma\'ut Haggadah: while the traditional Passover Haggadah does invite new ideas, they must take the shape of textual commentary or marginal discourses. In contrast, a successful Yom Ha\'Atzma\'ut Haggadah will be able to include new material, even on a yearly basis, just as long as the permanent textual selections are repeated every year, as befits a text that is meant to live within a tradition.Starting from the first years of the state\'s existence, several attempts have been made to shape the character of Yom Ha\'Atzma\'ut. Some of these succeeded, including the ceremony at Har Herzl, which opens the day, and the Israel Awards ceremony, which closes it. Others did not last. The attempts to compose a Yom Ha\'Atzma\'ut Haggadah are the most interesting. The number of such Haggadahs is not small, but it is not large, either. I own tens of such Haggadahs, and it is reasonable to assume that my collection is not comprehensive. Personally, I find each and every one of them interesting. I have edited a selection of passages from them in the past (Ben Haggadah le\'Atzma\'ut, Perakim be\'Toldat Ha\'Ra\'ayon shel \"Haggadah le\'Yom Ha\'Atzma\'ut\", privately published, Ramat Gan 2000), and I shall take a later opportunity to write about them at length, both descriptively as well as evaluatively. For the present I would like to mention two especially unusual Haggadahs. One was composed in Hebrew, but was never published. The other presents itself as based upon the former, but it only appeared in the English language and was published in the USA. I find both of them fascinating, and their comparison is instructive.I am referring to two Yom Ha\'Atzma\'ut Haggadahs that were written in a strictly religious context. That is their rare characteristic in the world of Yom Ha\'Atzma\'ut Haggadahs. Every Yom Ha\'atzma\'ut Haggadah reveals a clear connection to the Passover Haggadah, if it be through the use of four cups of wine, four questions of Ma Nishtana, the four sons, and so forth. It is rare for a Yom Ha\'Atzma\'ut Haggadah to be written by a real rabbinic personality for a religious audience, marking Yom Ha\'Atzma\'ut as a holiday possessing religious content - not just a religious flavor or style, but genuine religious significance.First, I came across the Haggadah for Yom Ha\'Atzma\'ut published by the \"Rabbinical Advisory Committee\" of the United Jewish Appeal in the USA in 1978. It is intended for a \"family, synagogue, or communal Seder in honor of Israel\'s Independence Day.\" Its first introduction is written by Rabbi Joseph Lookstein, chairman of the committee, a leading Orthodox rabbi in the USA who later became chancellor of Bar Ilan University. According to the introduction, it was Rabbi Lookstein who first thought of writing the Haggadah. He then brought up the idea before Rabbi Shelomo Goren, who was then serving as the Chief Rabbi of Israel. A surprise awaited me at this point of the story. The idea \"won immediate interest\" from Rabbi Goren, who was even willing to offer his active cooperation. The resulting Haggadah is \"based upon a text composed by Rabbi Shelomo Goren. In addition, the Haggadah includes an introduction (in English) written by Rabbi Goren himself.The formulation of the Haggadah is fascinating. For instance, it includes a new practice based upon the old custom of \"the fifth cup\" which I knew from the house of my father, Shimon Kasher and from the house of my grandfather, Rabbi Menachem Mendle Kasher (see his Haggadah Sheleima, pp. 161-178). It also includes, for example, a renewel of \"an ancient custom, the hanging of a meggilat mizrah\" on the wall facing Jerusalem. The Haggadah comes equipped with its own colorful meggilah upon which the verse from Isaiah (62:1) is written in decorative script: For Zion\'s sake I shall not be silent and for Jerusalem\'s sake I shall not be still, until her justice emerge resplendent and her salvation burn like a torch. I shall describe this Haggadah more fully elsewhere.From the moment I saw from the title page of the Haggadah that it was based on a Hebrew version written by Rabbi Goren, I sought to find the Hebrew original. Rabbi Goren\'s family members and students were unaware that he had composed a Yom Ha\'Atzma\'ut Haggadah. Even after they allowed me to search for it in his archives, I found nothing. Finally, after much toil, his family members found the lost document, the \"Haggadah for the Night of Yom Ha\'Atzma\'ut for the Thirtieth Year of the State of Israel\" written by Rabbi Goren. According to its short introduction, \"Its purpose\" was \"to lend the Atzma\'ut holiday a spiritual-national dimension, and to incorporate it into the stages of the vision of redemption of the Jewish People, and into the course of its history. Its practical aim is to establish a uniform family framework for the Atzma\'ut holiday, which had heretofore failed to consolidate a character, form, and content bearing religious, historical, and spiritual significance.\" The text of the \"Haggadah for the Night of Yom Ha\'Atzma\'ut\" is fascinating and even surprising when compared with the English Yom Ha\'atzma\'ut Haggadah. A detailed analysis is in preparation and will be published in the future. (I offer my thanks to Rabbi Goren\'s daughter and son for their efforts and for permitting me to publish the Haggadah. I am indebted to my friend Eli Har-Tov for his great help in this matter).Rabbi Shelomo Goren, the Chief Rabbi of Israel, and Rabbi Prof. Joseph Lookstein, paved sections of the road to the fashioning of Yom Ha\'Atzma\'ut in the spirit of the Jewish tradition. They imagined the desired destination of that road as \"a uniform family framework for the Atzma\'ut holiday.\" Today, it seems inescapable that we must change our picture of the final form of the holiday. There can be no uniform framework for all families; rather each family must preserve its own tradition. There can be no single text for all families; rather, there should be family texts preserved by family tradition; texts bearing clear resemblance to the Passover Haggadah on the one hand, while on the other hand they must also include much novelty and not a little flexibility, allowing renewal to take place in the body of the text itself, and not merely in its margins. The spectacle of hundreds and thousands of different Yom Ha\'Atzma\'ut Haggadahs will not only be breathtaking; it will also offer an opening for constant ideological and practical reinvigoration.Prof. Asa Kasher holds the Laura Schwarz-Kipp Chair in Professional Ethics and Philosophy of Practice at Tel Aviv University. Vered Levi-Brazili\'s (Hebrew) book, 17 Conversations with Asa Kasher, was recently published by Hotza\'at Kinneret, Zemorah-Beitan, Or Yehudah 2005. *********** Haggadot for the new Jew By Yair Sheleg \"How is this night different from all other nights? On all other nights since we came to this country we were under foreign, hostile rule that reined us in malevolently, and this night in our own state we are celebrating and we are able to redeem the wilderness and dry [swamps] ... On all other nights we are scattered in two separate camps - fathers from sons, and we all engage in the great work of building. This night we all recline at the same table.\" This quotation, which is taken from the Kibbutz Ma\'agan Michael Haggadah for 1949, typifies an outstanding aspect of the Passover Haggadot that were written in the kibbutz movement: the use of the traditional text, with \"adjustments\" to the spirit of the age - in this case, the first year of the establishment of the state. In the same spirit the Beit Ha\'emek Haggadah of 1951 inserted a new text into the story of the four sons: \"The wise son, what does he say? What are all the political parties, movements and factions that boast in our young country and interfere in matters of state at such a fateful time? ... The wicked son, what does he say? What do you need this work for? Every day there are new immigrants, who eat our bread and take our apartments ...- and just as he has removed himself from the community, you too must remove him from the community: In principle he is the type who loves only himself, the person who does not remember his own condition as a new immigrant.\" To the part about \"Pour out Thy wrath upon the gentiles,\" in 1945 Kibbutz Ein Gev added a sentence to mention the Holocaust that had only just ended and to say that the best thing to do is to drop the accounting with the gentiles and turn our backs on them: \"And those who have survived the terrible upheaval have resolved no longer to be in the shadow of the gentiles and to set their sights on the land of the Patriarchs that is being reborn.\" All of these quotations are taken from a luxurious album that has just been published, \"Yotzim behodesh ha-aviv\" (\"Going Out in the Month of Spring\") in which there are selected extracts and photographs from hundreds of kibbutz Haggadot that were written in this country since the inception of the kibbutz movement. (The publication is a cooperative project of four research institutes named after fathers of the labor movement: Yad Yitzhak Ben Zvi, the Ben-Gurion heritage Institute, Yad Tabenkin and Yad Ya\'ari.) Muki Tzur, a leading researcher of the kibbutz movement, is responsible for the contents, and the design - which is no less important - is the work of an artist and curator from Kibbutz Hama\'apil, Yuval Danieli, who has also added a brief analysis of the graphic element in the kibbutz Haggadot. During the research phase, Tzur combed through a number of the major archives of the labor movement, among them the holiday archives at Kibbutz Beit Hashitta and Kibbutz Ramat Yohanan, the archive of Hakibbutz hadati (the religious kibbutz movement) and the National and University Library in Jerusalem. He discovered more than 500 Haggadot, all of which were written during a relatively short period - between the 1930s and the 1960s. In his estimation, the total number is more like 1,000 Haggadot: \"We know that there are many kibbutzim that put out a lot of Haggadot in limited editions, only a few dozen copies, which never got to the major archives.\" For the sake of comparison: In the catalog of traditional Passover Haggadot prepared by Avraham Ya\'ari in 1960 that maps all the period from the invention of printing to that year, there are altogether 2,717 Haggadot. A short look at the \"sample pages\" from the Haggadot that appear in the boom explains the plenitude: Many of these Haggadot were not at all intended as sacred texts to be read year in and year out in the same way. Indeed, they look like a series of festive skits for Passover - and in any case they vary from kibbutz to kibbutz and from year to year at a given kibbutz. Only at later stages, when the kibbutz movement became established, did its various branches begin to publish standard Haggadot for all the kibbutzim that belonged to the same stream: the Kibbutz Haartzi Haggadah, the Kibbutz Hameuchad Haggadah and more. In fact, the production of the Haggadot themselves was already a relatively established stage of the movement. Tzur\'s research found that the first kibbutz Haggadah was written in 1928, about 20 years after the kibbutz movement was founded, and even it was not written by kibbutz members proper, but rather by members of a training group in Kolosova in Poland, who were waiting to immigrate to Palestine. The kibbutz Haggadot that were written here appeared only in the 1930s (first at Ein Harod). Before that, the kibbutz Seders where characterized by anarchism: The traditional text was open in front of them and here and there they even read from it, but the main thing was not the text - traditional or new - but rather the experience of togetherness, the singing and the dancing.The kibbutz Haggadah was in effect a symbol of the entire process of the Zionist revolution, and especially that of the labor movement: the creation of a \"new Jew,\" one who gives new and secular meaning to the Jewish tradition, its values and its holidays. Thus, they created new and timely versions of the traditional text, just as they inserted into the Haggadah completely new texts from the literature of the period. Tzur: \"The assumption was that Hebrew literature was a continuation of the canonical holy literature and therefore extracts from the new Hebrew literature are prominent in the Haggadot.\" The Passover Haggadah was especially apt for the labor movement people because it symbolizes the two freedoms they upheld: national freedom and social-human freedom - from the chains of enslavement. Tzur notes that the \"innovative\" Haggadah was indeed characteristic of the kibbutzim and the bodies that were influenced by them, like the training farms abroad or the soldiers of the Jewish Brigade during World War II, as well as the Jewish leftist movements in general, even those that were opposed to Zionism.

1957 Sedder ISRAEL INDEPENDENCE HAGGADAH English PHOTO BOOK Jewish JUDAICA:

$85.00